Welcome to all the new readers!

The end of the year is a great time to reflect. In this post we have two flavors of reflection: we’ll reflect on some of the companies I wrote about earlier in the year, looking at their more recent developments and how my arguments have aged as a result.

But first, some more personal reflections about The Flywheel itself:

Reflections on The Flywheel

Tl;dr, I plan to take The Flywheel to the next level in 2021 and I could use your help. Please take 5 minutes to fill out this survey!

This time last year I had recently left my job at Amazon, moved to Washington, DC, and was trying to figure out what I wanted to do next.

On paper the story is more or less the same today. I am once again unemployed after, once again, leaving Amazon.

But life doesn’t happen on paper, and in reality my life has transformed a ton in 2020. The Flywheel has been a huge part of that transformation.

I won’t get into all the details here. If you’d like to learn more about my personal story, feel free to check out a recent interview I did on the Joseph Wells Podcast. Instead I want to briefly talk about where we’ve been and what’s next with The Flywheel.

The Flywheel in 2020

The Flywheel has been one of the most pleasant surprises in my life. I published the first piece on August 25th when my list had 6 emails on it (including my own). Writing was something I had thought about doing for a while, and publishing it was more about proving to myself that I wasn’t totally full of crap than anything else. The response has totally blown me away.

Since then, I published 7 more deep-dive articles plus 1 interview transcript, working up to a once-every-two-weeks cadence. My email list has grown to nearly 2,400 (and my twitter following to almost 1,300, all from basically 0), all with strong engagement (open rates exceed 55% almost every time—I’m told this is good for email).

Even more exciting are the less quantifiable things that have happened. I’ve met dozens of smart, kind, humble people who are becoming collaborators, clients, and friends. It’s given me the opportunity to rekindle connections with old friends, too. I didn’t start The Flywheel to become a professional writer per se; rather, I wanted to leverage the serendipity of the internet. On that measure, it’s been a smashing success, and now it has me thinking differently about my future.

The Flywheel in 2021

As I look to the future, I think of two main priorities for The Flywheel in the upcoming year:

Priority 1: Find the right balance of cadence, topics, and format

Thus far, The Flywheel has primarily been a series of long-form, company deep dives. While growth has been tremendous, I have found that momentum dips between my fortnightly publish dates. I want to publish more frequently, but am leery of committing to doing a full deep dive every week.

So the goal is to publish more without burning out. To that end, I plan to get a bit more experimental in the first half of 2021. I have a few great interviews lined up, and am in the early stages of exploring some new collaborations as well. I have ideas for new formats (more interviews, guest posts, more ‘company X revisited’, etc), and I’ll rely on your feedback as I try new things out.

Priority 2: Get serious about monetization.

I didn’t set out to make money from The Flywheel, but it does take a lot of work, and I don’t currently have another source of income. I’d love to spend more time writing more thoughtful deep dives—even if it isn’t a full time thing just yet—and financial support would enable me to do so.

Newsletter writers broadly have two options when it comes to monetization: paywall or ads. I am not particularly drawn to the paywall model, because I think it changes the expectations around the whole thing. I don’t want to say that I will never go that route, but it almost certainly won’t be in 2021.

That leaves me with ads. Yes, the ad-based model of internet media has essentially broken the world, but my sense is that there’s a tasteful way to do it. My plan is to promote products I either use personally or otherwise have a personal connection to. I plan to also start offering companies the opportunity to pay to be featured in a full deep dive article about their flywheel. My pledge to you is that I will always be honest about anything I promote and how I’m getting paid.

If you know any companies who might be a good fit for sponsorship, just reply to this post or send them this intake form.

Help me accomplish my goals!

I’m sharing because I want to be transparent, but also because I could really use your help on these fronts. I put together a 5 minute survey that will allow me to collect reader data and feedback. The feedback will be used to help accomplish priority #1, and the data will allow me to better attract advertisers for priority #2.

If you’ve enjoyed The Flywheel, please take a few minutes and tell me about it here:

Onto the end of year update!

Reflections on Previous Flywheel Companies

Every public company is required to disclose certain standard metrics, like revenue, cost of goods sold, net income, in its quarterly and annual documents. Most public companies also elect to define non-standard metrics: KPIs they might use internally as signals of progress. These secondary metrics are business drivers that are leading indicators to the more standard metrics like revenue and profit. For example, Peloton reports its number of Connected Fitness Subscribers every quarter. They don’t have to, but they do.

One of my favorite things to track is the way companies discuss these metrics over time. I find it intriguing because in some boardroom at some point in time, there’s some multi-dimensional chess being played. When a company decides to include an internal metric for the first time, they’re signing up for Wall Street’s scrutiny of said metric. They better be pretty confident that they want to continue reporting that metric indefinitely, because the absence of that metric—or a rewording of how they describe it—next time will raise eyebrows.

And so it is that we revisit two companies whose Flywheel writeups centered heavily around secondary metrics.

Peloton’s COVID Quarters

If you haven’t yet read The Flywheel #1: Peloton’s Food Network Opportunity, feel free to check it out for full context before diving into this update.

My earlier Peloton piece was published on August 25th, about two weeks before the company reported the results of its first full COVID quarter (from March-June, AKA its fiscal Q4). It has since also released its July-September (Q1 2021) earnings.

As expected, results from these two quarters were massive. In both quarters, revenue was up around 200% YoY, and the company achieved profitability for the first time.

In addition to these results, the company also had a major product launch: the Bike+, which features better speakers and a screen that now turns 90 degrees to the side. I suppose the theory was bike owners would be more likely to utilize the full suite of workouts available on the platform if the screen could turn even a little bit.

From an investor perspective the Bike+ is notable because of its price: it’s an increase of about $200 from the original bike price, and demand hasn’t seemed to slow one bit. It’s a good sign that Peloton can increase the price with almost no impact to demand.

Naturally, PTON the stock has been one of the year’s darlings on Wall Street. When I wrote the original piece the stock was already up over 100% YTD. Since then it’s only gone up another 200% or so.

But there are causes for concern that are worth keeping an eye on as we head into 2021: (1) profitability has arrived but it might not be sustainable, (2) reliance on hardware, and (3) engagement question marks.

Profitability

As mentioned, Peloton experienced its first ever profitable quarter and then repeated the feat. Perhaps it’s not surprising that given everything going on with COVID that one of the hottest companies out there would find a way to spin up a profit.

What is a little surprising—and a little concerning—is that profitability has seemingly come as a direct result of the company’s reduction in operating expenses (OPEX) spend, rather than some change in the product’s unit economics. Peloton’s OPEX primarily comes from sales & marketing and general & administrative. Both have been cut by about 50% relative to revenues compared to the previous year.

Meanwhile, gross margin (i.e. the profit left after the direct cost of the bike or tread has been accounted for) has remained basically flat, around 40%, or even down (-6% YoY in the most recent quarter). I think partly this validates my claim in the original article that the standalone digital subscription is really not contributing much to the company’s bottom line. Digital revenues have a much higher margin than hardware, but subscriptions as a percent of total revenue are actually 30% lower than they were in the previous year.

It reminds me a bit of DoorDash’s S-1, which I wrote about: if Peloton is only profitable because it slashed marketing spend during COVID, then that leaves the obvious question of what comes next. Not only are in-person alternatives going to become available, but the competition is also heating up.

Hardware

That leads us to hardware. In the original piece I argued that Peloton needs to reduce its reliance on producing hardware hits and shift its focus to building social and other network effects and investing in its talent. In other words, it needs to build unique advantages that will allow it to sustain for decades.

We’ve seen no signs that they’re listening to me. Instead, they’re doubling down on hardware. We mentioned the Bike+, but Peloton also announced a new, cheaper treadmill (supporting my speculation that treadmill v1 was a flop).

Furthermore, Peloton announced a deal to acquire Precor, a company whose name you might recognize if you’ve ever worked out at a hotel gym. Peloton is acquiring Precor’s production capability and relationships with corporate customers. Peloton has a short term problem fulfilling customer demand, and Precor won’t solve that. The deal is only expected to contribute to fulfilling end customer demand at the end of 2021. It also won’t help it become the type of fitness platform it dreams of being.

Back to competition: with Apple Fitness+ recently launched, and Lululemon ramping up its plans for Mirror, the competitive landscape is only getting tighter for Peloton. When CEO John Foley isn’t drinking water like a serial killer or jogging in his bathroom, I hope he’s thinking about more than just hardware when he worries about his user engagement.

Speaking of which..

Engagement

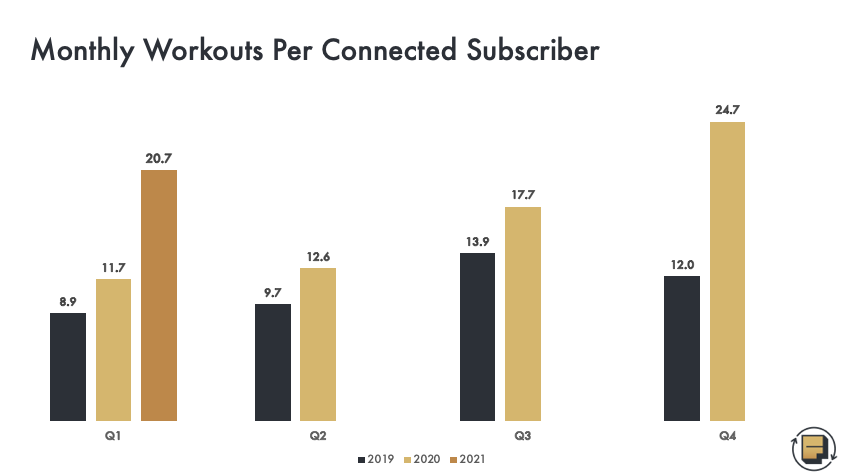

Now we get to Peloton’s secondary metrics. In my original post, I mentioned Peloton’s ‘Monthly Workouts per Connected Subscriber’ metric, and how the fact that it was improving over time suggested the existence of a flywheel. I’ve updated the graph I showed there to include the two quarters since:

At first glance, this looks encouraging. YoY ‘monthly workouts’ continues to rise, and quickly. But it also raises some questions.

What’s actually going on here? Did people really work out 2x more in Q1 this year than they did last year? Or is Peloton seeing a larger share of multi-user households given the pandemic (the wording seems to suggest that this number is computed based on households, not users)?

Maybe there’s a timing question: if new users are more engaged, then the fact that there have been a ton of new users might inflate the average. In that case, perhaps a cohort view would be more appropriate.

That’s the thing with secondary metrics: sometimes they raise more questions than they answer. And the story Peloton is trying to sell us—that people are engaging more with Peloton as time goes on—hinges entirely on the answers to these questions.

The company is surely capable of producing this analysis on a per-user basis, or with a cohort view, and has chosen not to for some reason. It’s entirely plausible that there’s some unspoken stuff hidden inside of this metric, and that Peloton just doesn’t want us to probe too deeply.

We’re already starting to see signs of both potential softness in engagement and Peloton’s manipulation of the storyline: if we look at the change between Q4 (March-June) and Q1 (July-September), we actually see a decrease of about 4 workouts per month.

Peloton explains the decline as normal. In its Q1 2021 shareholder letter, the company writes: “reflecting typical seasonality, Member engagement eased modestly from Q4 FY 2020, but remained well above year-ago levels”. Reflecting typical seasonality? Really?

The previous ‘season’ saw a decline of 2.5% from Q4 to Q1. This time around, the decline was 16%. I don’t know why engagement declined this year, but there’s no apparent basis to call it typical or seasonal.

This is the danger of secondary metrics. Once you start reporting them, you kind of have to keep reporting them, even when they don’t make you look good. And if you try to use BS to explain them away, they’re easily caught by The Flywheel’s BS detectors.

I don’t know whether Peloton is deliberately misleading us, or well-intentioned but delusional. But it’s one of those two, and neither is good news for the company moving forward.

Stitch Fix’s Short Squeeze

My Stitch Fix article was the first and only nakedly bullish piece I’ve written so far (aside from my piece on On Deck, a private company). In it I argued that the company was under-appreciated, and that it was in the process of establishing a flywheel that—with enough patience—would reward shareholders mightily.

On December 7th, Stitch Fix reported its Q1 2021 earnings, and the stock shot up 40% the same day. Since then, it’s only continued its ascent, gaining another 40% or so for a total increase of almost 100% since my article.

It was hard not to gloat, and I got a bunch of ‘thank you’ texts from friends who bought SFIX after my piece came out.

But the truth is: it caught me off guard. My argument was that patience would be required for anyone believing in Stitch Fix, and yet here we were with the type of stock move that suggests the future arrived early.

Did I miss something in the analysis that made the company a slam dunk in the short term?

In its quarterly letter, Stitch Fix talked about the secondary metrics I mentioned in the article, and of course its primary metrics as well. Let’s recap:

Secondary Metrics

My Stitch Fix thesis focused heavily on the Fix success rate. Specifically, the fact that Fix success was increasing over time, I argued, was a proof point that the company’s data science machine was working. Moreover, I argued it will enable Stitch Fix to pour gasoline on the customer acquisition bonfire once it reaches a critical threshold of First Fix Success, i.e. the percentage of items kept by customers in their first interaction with the company.

Both of these secondary metrics are featured prominently in the latest quarterly report. First Fix Success (i.e. the percentage of first Fix’s that sold at least 1 item) approached 80%, the highest level in about 5 years—although SFIX doesn’t actually report this metric every quarter, so we have to take their word for it.

Re: overall success rate, the company states that it reached record highs in Q1 as well, without explicitly reporting a figure.

Remember, companies aren’t obligated to report secondary metrics consistently. That’s what makes them secondary.

Stitch Fix doesn’t always report the numbers, and when it does it does so using different language. I am inclined to believe that withholding information is an admission of softness in that information. But we just saw with Peloton that reporting information consistently can lead to issues as well.

Damned if you do.

Primary Metrics

For Stitch Fix, Q1 2020 represented a rebound from the COVID beating it took earlier this year. Revenue growth returned to double digits, and profitability rebounded to positive once again. All signs are that it has not only survived COVID, but that its long-term, data science backed march is back on track.

Is the bounce merited?

These results are nice, but they are aligned with my analysis—that Stitch Fix is a solid long-term bet—moreso than the idea that Stitch Fix hit an unexpected home run during this most recent quarter.

So what gives? Why would a stock pop 100% in 3 weeks on such a steady result?

The answer: short squeeze. It’s the only explanation that makes sense. Stitch Fix was until recently a favorite among short sellers (i.e. folks betting the price would go down). From Barron’s: “more than 37% of Stitch Fix shares available to trade are sold short—the average for a stock in the S&P 500 is closer to 2%”.

When Stitch Fix earnings showed the company’s resilience, short sellers freaked out and attempted to cover their positions. The only way to do that is to buy shares, which bid up the price of the stock.

Is it the most satisfying explanation? Maybe not. But we’ll take it.

The Flywheel is not explicitly an investing newsletter, nor do I advise anyone to buy or sell based on my articles. But I still believe Stitch Fix is a solid long term investment. This quarterly earnings only bolstered that opinion. And as happy as I was with the recent move, it is not a reflection of my argument coming to fruition about a decade early, but rather just a bunch of the haters shifting over to the good side.

That’s it for The Flywheel in 2020. Thanks so much for everything. If you’re reading but haven’t subscribed, you can do so using the button below. And let me know what you thought of this piece on Twitter.

As this is a new format for me, I’d appreciate it if you could provide some feedback. Would you like to see more of these recap articles? Let me know using one of the links below.