Welcome to the 361 new subscribers of The Flywheel since last time. If you’re reading this but haven’t subscribed, click below to join 2,146 of your smartest friends and peers who receive The Flywheel in their inbox every other Tuesday.

Today I’m excited to bring to you a Flywheel first: a special collaborative article. I co-wrote this piece with Sid Jha, a writer and friend who publishes a wonderful weekly blog called Sunday Snapshots every, you guessed it, Sunday. It’s well worth a read and—if you’re so inclined—a subscribe.

When lululemon acquired Mirror this past summer, the joke was that now lululemon customers finally have an overpriced mirror to go with their overpriced leggings.

lululemon (yes, with a lowercase ‘l’) has become the go-to brand for much more than just yoga pants. Outerwear, work-pants, and of course, workout clothes of all types, for both men and women. And now the company is acquiring futuristic home workout tech companies.

But it was not at all obvious that this is where the brand was heading, even as recently as late 2018. In fact, around 2014-15, the company was starting to stall out, its stock price was on life support, and its CEO was being ousted for fat-shaming women who didn’t quite fit into lulu’s overly tight customer segmentation.

If someone had told me then that my dad would be wearing lululemon every day, I’d have imagined a late-middle-life crisis involving yoga retreats in Bali.

Since 2018, the company has been on a tear. It’s not often talked about as a turnaround story, but that’s exactly what it is.

In 2018 lululemon’s revenue growth rate exceeded 20% for the first time since 2012, and its market cap as a percentage of Nike’s market cap (a metric we invented) went from 8% in the middle of 2017 to 26% today. The chart below shows us the rise and fall and rise again of lululemon over the past ~10 years.

In this piece we’ll explore how and why lululemon was able to achieve the success it’s enjoying today, and what the Mirror acquisition suggests about the future of the company.

The Power of Three

Unlike many other stocks that have done well in 2020, lululemon is hardly an internet-first brand. In fact, it is even older than one of the two writers of this piece. And while there’s no doubt people are wearing their home-clothes more frequently these days, the lululemon recovery predates COVID. Below is a chart of its stock price performance between 2014 and January of 2020:

So what’s behind the comeback?

Management will say it’s about the “Power of Three,” its 5 year plan that was “unveiled” in 2019:

Product Innovation: Double the size of its men’s revenues by 2023. In addition, its plans call for continued expansion in the women’s and accessories businesses, in particular by offering more sizes for women of all shapes.

Omni guest experiences: The Company expects to more than double its digital revenues by 2023.

Market expansion: The Company plans to quadruple its international revenues by 2023. The Company’s recent success in its international markets demonstrates that the “sweatlife” translates across cultures and geographies and presents considerable growth potential for the brand.

One cannot find a statement by a lululemon exec since 2019 that fails to mention the Power of Three. Much like the “Conjoined Triangles of Success” by the fictional Jack Barker, the Power of Three appears at first glance to be mind numbing, corporate jargon at its most boring.

Product innovation, omni-guest experience, and market expansion could be the growth pillars for almost any company in the world. If your corporate strategy looks like you copied and pasted it from Googling ‘best corporate strategies,’ it’s not a great look. But there’s something unexpected beneath the surface.

Omni-guest and market expansion are important to lululemon, but we think they’re not as interesting as the real key here: product innovation. Usually when a large brand talks about product innovation, they are referring to new colors of existing products, or new flavors of toothpaste. But in this case, lululemon is referring to a completely new customer segment: men.

lululemon’s ability to shift towards men (21% of sales were from men in 2019, up from about 0% in 2015) is the real key to understanding lululemon the brand, and provides a big clue towards the unstated rationale behind the Mirror acquisition.

lululemon’s brand flywheel

In order to understand how lululemon was able to go from being the yoga pants brand to a brand that men of all ages turn to for work pants, we need to go back and understand what kind of brand lululemon built to start with.

lulu the brand

The original image of lululemon is something as simple as workout or yoga clothes.

Their incredible growth story has come from expanding beyond their core customer of yoga studio-going suburban moms to everyone from Jake’s dad who swears by his ABC pants to Sid’s girl friends who would not be caught dead in the gym without their black, red, and white tote bag covered with chic lettering.

It seems counter-intuitive. A young professional does not want to be associated with the suburban mom. And the suburban mom does not want to be associated with the young professional. But they both want to be associated with lululemon.

How is it possible? Classic business wisdom tells you something along the lines of “you need to have a coherent brand strategy” or “you cannot be everything to everyone.”

But somehow, lululemon really is a different thing for different people. It’s an incoherent brand. They are equally the go-to for women’s bras as they are for men’s slacks.

They’ve done it by deemphasizing athletic performance and focusing on fit, comfort, and aesthetics.

Let’s compare lululemon with Nike once more. Nike spends over $6B a year on athlete endorsements. The message with Nike is clear: if you want to hit a tennis ball like Serena, kick a ball like Cristiano, or Be Like Mike, you need to wear Nike.

lululemon is different. Their corporate ambassador’s page includes mainly yoga teachers, but also musicians, meditation teachers, kayakers, and other generally cool, chilled out people. To the extent they do have representatives from popular sports leagues, it’s people like Chandler Parsons, an NBA player who hasn’t been a starter in the league since 2016. Hardly someone who’s athletic achievements little kids everywhere want to emulate.

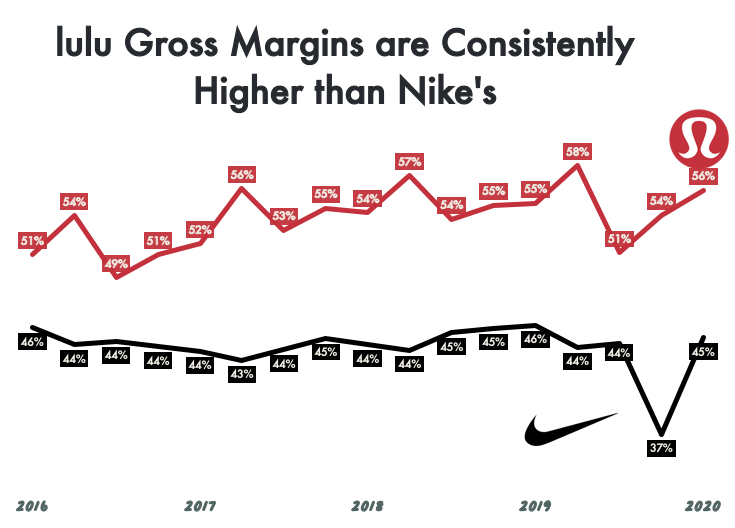

And it’s not like this different positioning came at the expense of pricing power. Au contraire! Anyone who has shopped at lululemon has likely marveled at how the company has normalized spending $98 on yoga pants, $128 on casual pants, and $148 on hoodies. Compared to Nike, lululemon has enjoyed stronger gross margins (a good proxy for pricing power, especially for companies who sell physical products) for years:

lululemon’s flywheel

Every great brand communicates something very clear to customers: I will satisfy this need for you. lululemon deliberately positions itself as an amorphous product: you can feel great wearing its clothing, whatever that means to you. The need it satisfies is highly personal to each and every customer.

In a piece about flywheelsThe Flywheel has referenced before, Max Olson describes a type of flywheel he calls the Brand Habit flywheel. In this flywheel, customers associate a brand with a specific value proposition based on the need it solves (with an assist from sticky marketing). As this association strengthens, customers increasingly stop searching elsewhere for a different solution and therefore purchase more frequently from that brand. In turn, this cements the association between the brand and the value proposition, like how people view Amazon and online shopping, Google and search, etc.

The story is no different for lululemon and women’s yoga pants. lululemon created the category of yoga wear, and used a powerful combination of community marketing and functional, technical excellence to establish a dominant position in that market. It didn’t take long before of course you buy your yoga pants from lulu. This caused people to do more yoga, which caused more people to buy from lulu. As more customers purchased from lulu, they could invest more and push the boundaries of athletic wear, inventing new fabrics and styles that met the customer needs even more effectively.

What’s unique about lululemon that other powerful brands, say, Coke couldn’t achieve, is that they were able to expand to adjacent and increasingly unrelated products without hiccup, and without changing the brand. It’s not unusual that lululemon attempted to go after men. It is unusual that lululemon went after men under the lululemon brand, with lululemon stores, and without sacrificing its core lululemon business. The name is lululemon for pete’s sake!

They did this by being unspecific about the job-to-be-done of lululemon. The brand wasn’t ever about being the most technically sound yoga pants, but rather about being the most comfortable pants for anyone. With that positioning, it makes sense that the company was able to shift its target customer without hiccup.

Let’s revisit the Power of Three corporate strategy: when lululemon talks about product innovation, they mainly are talking about men. We’ve shown why they have been able to appeal to men so successfully. But the Power of Three takes the company to 2023. What happens next? This is where the Mirror acquisition fits in.

lulu x Mirror

After lululemon acquired Mirror in late June, the reactions fell into one of two camps.

Camp 1: lulu’s weak attempt to become Peloton

This camp believed that the acquisition was merely a reflection of the times, a desperate attempt (and heavy overpay) by lululemon to capture its share of the sharp shift to at-home workouts spurred by COVID, perhaps even a lashing out at Peloton.

There are a couple of problems with this narrative: first, Mirror’s previous valuation was $300 million, in a Series B that closed one year prior to the lululemon acquisition. Even without a COVID bump, a 60% increase in valuation from one round to the next is not outrageous. With the COVID bump, one could argue that lululemon actually underpaid.

The other, more glaring, problem is that lululemon invested in Mirror shortly after that series B round in 2019. Clearly, lululemon had its eye on Mirror even before COVID.

The final nail in the coffin for this camp is that lululemon had, before Mirror, never acquired another company. It’s hard to believe that an experienced executive team would pull the trigger on its first ever acquisition essentially as a freak out in reaction to COVID.

Camp 2: lululemon + Mirror > sum of their parts (AKA synergies)

This camp believes that the acquisition was a wise move by lululemon, but for all the sort of obvious reasons we might imagine—the classic ‘synergies’ that are salivated over in any notable acquisition. This camp suggests that Mirror can achieve a much higher ceiling as part of lululemon than it ever could on its own. For one example, Mirror can leverage lulu’s stores as “free” distribution, an option previously unavailable to it.

For its part, lululemon gets to vertically integrate and enter into a deeper relationship with its customers. After all, if customers are buying lululemon to work out, why shouldn’t lululemon see a cut of that workout revenue? As CEO Calvin McDonald said after the deal closed, ““We will have a place in the home, there’s a huge advantage for our brand.” There are ample opportunities for lululemon to convert its regular customers to Mirror customers and vice versa.

Noted brand expert Web Smith laid out the case for this camp on Twitter:

I don’t necessarily disagree with this interpretation: the opportunities will be numerous and interesting. For instance, whereas before lululemon could host a yoga class in-store, now they could host a Mirror class in-store, and convert some of those customers to a recurring revenue subscription.

But this analysis misses the point to a large extent. First, the sheer number of Mirrors that lululemon would need to sell in order for this to have a large impact seems unrealistic. Mirror is estimated to bring in $100-150M in revenue in 2020. Using some back of the envelope math that you can check out here, we can estimate that Mirror has somewhere between 50-100K customers. Even if lululemon sees a $100 lift in spend (on average) from those customers, the $7-10M revenue bump is too small to be felt by a $4B revenue company like lululemon. Even if Mirror could 10x in the next 5 years, 70M-100M is just not a needle mover.

If we can do this type of math, so can the CEO of lululemon. This is why we believe there’s more to the story than meets the eye. And it wasn’t until we learned about Whitespace that we developed our own theory as to why lululemon would acquire Mirror.

Whitespace

In 2018 Fast Company wrote a detailed article about lululemon’s secretive product development lab, known internally as Whitespace. It’s one of the only—and certainly the most in-depth—write ups about Whitespace out there. Whitespace is a high-tech laboratory set in a basement in Vancouver, lululemon’s HQ.

The central thesis behind Whitespace, and by extension lululemon’s product development, is that each individual moves differently, and therefore has unique apparel needs. Chief scientist Chantelle Murnaghan said, ““It turns out that the way that each person moves is entirely unique to them. It’s like a fingerprint.”

From the FastCo article: “The brand would create bras for high-impact sports, like running, and then include more compression in bras for larger-busted women, who experience more breast movement. But when lululemon carried out its own research, it found that two women with a 36C bra size experienced different breast motion as they moved.”

This type of insight led to the ‘Like Nothing Bra’, which took 4 years to develop: “the Whitespace team discovered that female consumers were searching for a bra that felt like being naked, but that still provided support during exercise. There was nothing within its current line that was specifically designed to create this sensation“.

If lululemon can understand these individualistic needs at a physiological and psychological level, goes the theory, it can invent new products with new fabrics that nobody else can, and stay ahead of the curve. It could even transform itself from a yoga pants brand for slim women, to one that men love for business casual pants.

A Whitespace in every home

In the Whitespace lab, lululemon has a special treadmill on which test subjects can walk or run on. Using cameras and sensors, the team is able to identify the specific fingerprint of the subject’s motion, and determine their unique needs. lululemon at one point was preparing to bring the Whitespace treadmill experience in-store, which in theory would enable employees to make better recommendations.

This is why we believe lululemon really acquired Mirror: to accelerate their plans for Whitespace by putting a version of it in customers’ homes. Yes, there will be cross-selling opportunities and other synergies, but the aggregate dataset is the real prize here. lululemon will be able to see how people move in the tens or hundreds of thousands, and be able to close the loop on how (or if) the apparel they wear influences that movement.

It’s unclear to me—and probably to lululemon—specifically what that might look like, but that’s part of the point. It’s a data collection play, and you cannot presuppose what the data might tell you.

If this is all true, then the Mirror acquisition is the polar opposite of a short-term reaction to COVID, or an attempt to keep up with Peloton. Sure, maybe the base case argument for this acquisition is that lululemon will breakeven on the synergies we described above.

But the bull case is one nobody is talking about. The bull case is that Mirror is the gateway to the next big product innovation unlock after the menswear opportunity starts to slow down. Even if there’s only a 20% chance that the Mirror data play bears such fruit, if it leads them to its next frontier, it will have been $500M well spent.

That’s it for this edition of The Flywheel. Thanks so much for reading. A huge thanks to Tanya, and Tom for helping out with this one.

If you liked this article, smash that like button and share with a friend! Let me know your take on Twitter here.

Great write up. Super interesting bull case