Zillow and the Innovator's Dilemma

Why Zillow was willing to risk a perfectly fine flywheel for a much more complex and risky one.

Welcome to The Flywheel, where we take a deep look at a company’s business and products to understand which areas are spinning smoothly and where a little grease may be needed. If you’re reading this but haven’t subscribed, click below to join 1,228 of your smartest friends and peers.

To my U.S. subscribers: if you’re reading this on Tuesday and haven’t voted yet, please do that now! You can read this while waiting in line or after you get home. PLEASE VOTE! And if you’re looking for more of an election distraction after reading this article, I've been enjoying For the Love by branding expert Aja Singer (not related!). Check out her recent post on how DTC brands leverage magic to grow into big, meaningful companies. Onto the Flywheel.

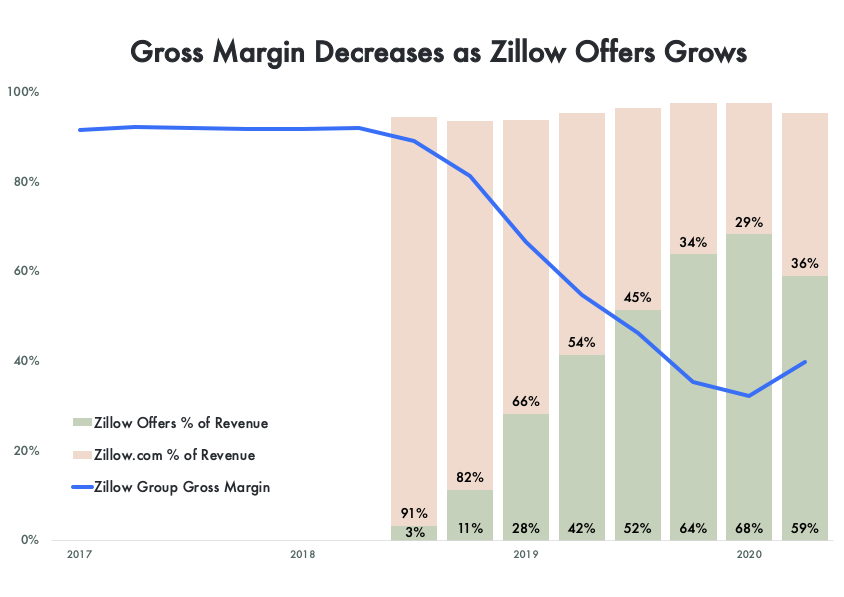

Let’s play fantasy CEO. The year is 2018, and you are the CEO of a roughly $1B-revenue, public company whose gross margins and revenue growth over the past 3 years looks like this:

What’s your first reaction to this chart? Is it, “nice! Let’s keep this party going!” or perhaps a slightly more cautious, “not bad, but let’s make sure we understand why growth is starting to slow down”?

If your name is Spencer Rascoff and you’re the former (is that a spoiler?) CEO of Zillow Group, your reaction is more extreme than either of those. In fact, Rascoff and the Zillow board decided to go ballistic on that previously slow and steady trajectory. I was able to obtain some actual footage of the board meeting in question:

Zillow’s Left Turn

The innovator’s dilemma is a concept describing how incumbent companies are vulnerable to disruption. Under the theory, big and established companies develop blind spots that lead them to ignore or be otherwise unable to respond to emerging competitors. The canonical example is Blockbuster and Netflix. Companies tend to be unwilling and/or unable to upend their existing business models—their flywheels that are spinning smoothly—to gamble on small but fast-growing ones.

Zillow spotted the threat posed by an up-and-coming company called Opendoor and made a sharp left turn in Q2 2018 to launch Zillow Offers. Zillow Offers enables home sellers in a small but growing number of cities to receive an instant offer from Zillow. If an offer is accepted, Zillow will buy the home outright, hold it for a period of time while doing some basic maintenance, and then sell it to a new buyer. This practice is known more widely in the industry as iBuying.

How fundamentally did this change Zillow’s business? Here is the same gross margin data brought forward to today, with an overlay of Zillow Offers as a percentage of total revenue:

Ever wonder where I get my public company data for these great looking charts? I use HyperCharts, a service that aggregates data for top public companies and presents them in a series of easy to consume charts. HyperCharts is great if you want to stay on top of the companies you’re analyzing or investing in.

If you use my link and eventually purchase a premium subscription, HyperCharts will share a portion of that revenue with me. It’s the best way to get information to inform your investing, and a fantastic way to support The Flywheel.

These figures emphasize just how different iBuying is from Zillow’s core, ads-based business. Zillow has gone from a mostly automated world where an agent can pay the company without a single human getting involved, to one in which they now must manage an army of people who inspect, buy, repair, and sell homes. Zillow’s core business gross margin is over 90%, and Zillow Offers’ gross margin is between 0-5% depending on the quarter. Just about the only thing the two businesses have in common is that they are both technically in the real estate industry.

If it were only that the businesses were operationally different, we might think that wasn’t such a big deal. If a startup can learn how to operate a new business, surely Zillow can too? But it’s worse than that. By launching iBuying, Zillow entered into direct competition with sellers’ agents. And that’s a problem because sellers’ agents are Zillow’s main customers. Before iBuying, over 80% of Zillow’s revenue came from seller agent advertising fees.

Zillow decided to enter not only a significantly more complex business, but one that represents a potentially mortal threat to its largest revenue source. I’d call that blowing shit up. Apparently the board recognized how momentous a shift this would be, and replaced Rascoff with the original founding CEO of Zillow, Rich Barton.

Back to the innovator’s dilemma: the history books are full of companies who ignored the upstarts and ended up dead. I don’t know of too many examples where a company did what Zillow did. To that extent, they should be lauded. But under what circumstances does it make sense for companies to attack a threat head-on, and when should they be more cautious?

My goal in this article is to find some answers in the flywheel. We’ll start with Zillow’s pre-iBuying flywheel and then look at how iBuying fits in, if at all.

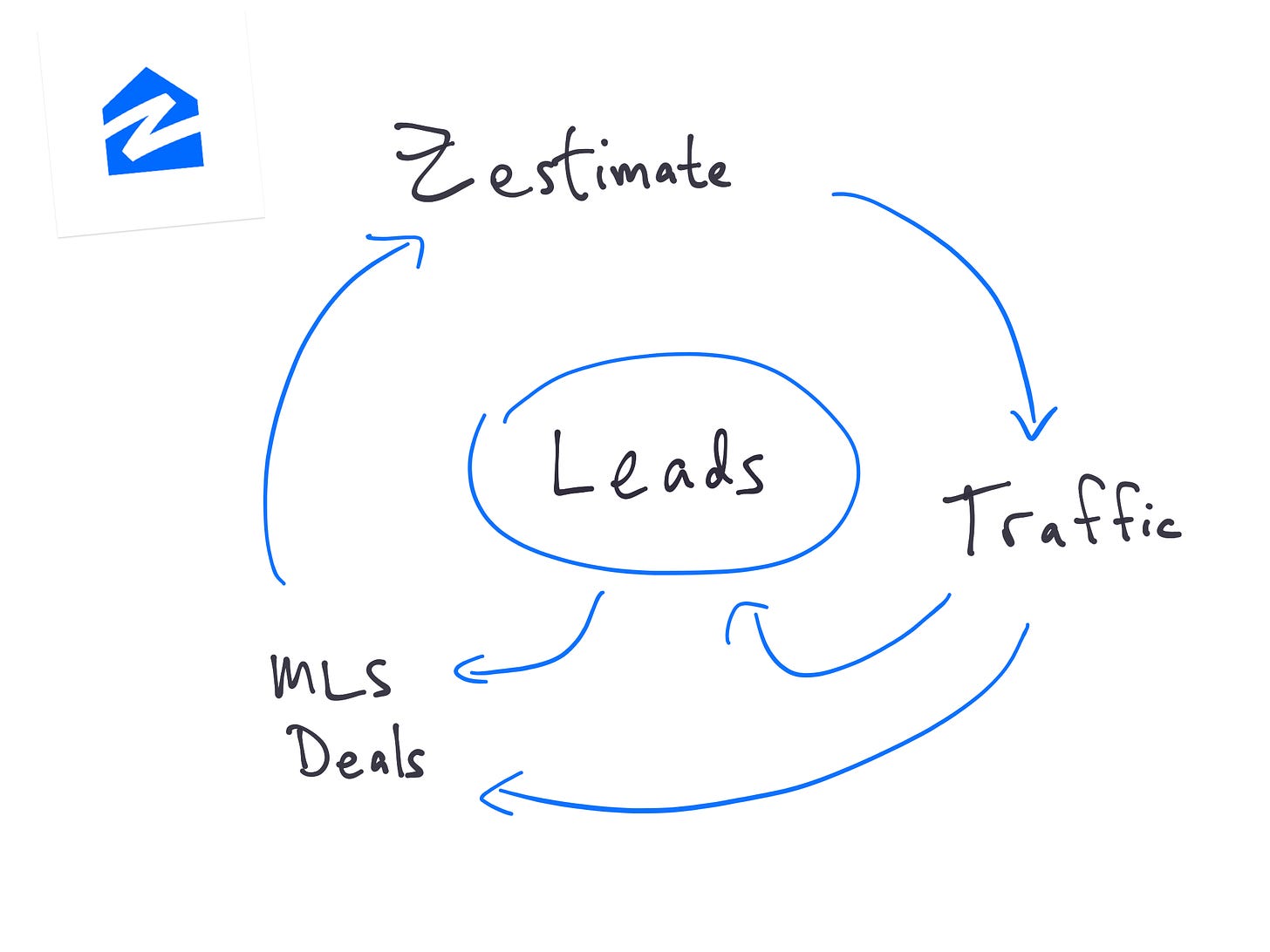

Zillow’s Pre-iBuying Flywheel

Zestimate

Zillow first launched in 2006 as an auction service for homes. The idea flopped, but through the process, Barton and team stumbled upon a hit: the Zestimate. At first, it was totally inaccurate, but people loved the idea that you could see an estimated value for pretty much every home in America.

Over time, the Zestimate became a major force in US real estate. I remember looking at houses for fun in Seattle a few years ago and being told that sellers would refuse to accept Less Than Zestimate. It struck me then that although Zillow’s influence on the market was somewhat artificial, it was nevertheless substantial.

Traffic

The success of the Zestimate brought eyeballs. All of the eyeballs. Zillow’s traffic has grown from 54M unique monthly users in 2013 to about 200M in 2019. Zillow became the most popular place to begin a home-buying or renting journey, which meant that Zillow was also the most important place for a home listing to appear.

And Zillow did what any company receiving an unholy amount of traffic would do: sell ads. Or as they are known in this business, leads.

Leads

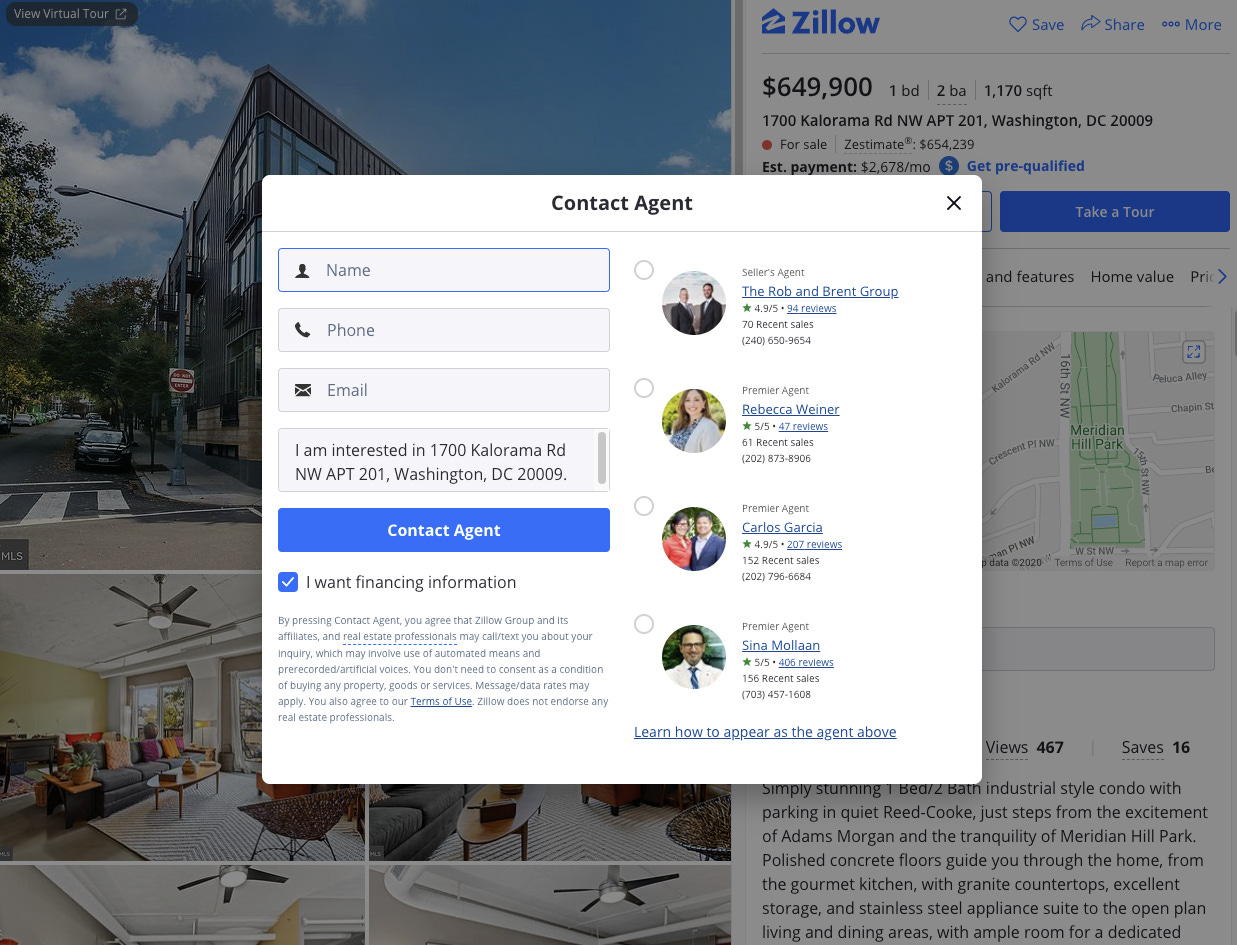

Zillow built a big business around generating leads for real estate agents. Agents pay to appear on Zillow’s listings pages, like the one below:

This became Zillow’s core business. As Zillow generated—and over time, qualified—more leads for agents, it found itself in an interesting place. Zillow originally set out to disrupt the real estate market, but by hitching its wagon to the fate of real estate agents, Zillow ended up reinforcing the status quo. The interests of real estate agents became the interests of Zillow.

Multiple Listing Services (MLS) Agreements

Of course, that wasn’t all bad for Zillow. At first, Zillow relied on home sellers to upload information about their houses directly to Zillow. In this context, Zillow pitted itself as a rival to the MLS around the US.

The MLS have been an important gatekeeper in the real estate industry for as long as there has been a real estate industry in the U.S. Per the National Association of Realtors (NAR):

“In the late 1800s, real estate brokers regularly gathered at the offices of their local associations to share information about properties they were trying to sell. They agreed to compensate other brokers who helped sell those properties, and the first MLS was born, based on a fundamental principle that's unique to organized real estate: Help me sell my inventory and I'll help you sell yours.”

The MLS helped agents create value by making home data scarce and difficult to access; Zillow was making it open and free. As Zillow grew in popularity, however, MLS realized they couldn’t live without Zillow. Zillow began to sign an increasing number of deals with the various MLS in the US. Now with every listing, Zillow’s data advantage became truly insurmountable, which fed back to the Zestimate making it increasingly accurate as time went on.

Zillow’s Post iBuying Flywheel

Aside from how much less clean and simple this looks, the main trouble for Zillow is that the iBuying flywheel—from what I can tell—doesn’t really feed back into the main flywheel.

Offers Made

Zillow’s main advantage with iBuying is its enormous traffic, and therefore customer acquisition, advantage over anybody else. With more traffic, Zillow can present its Zillow Offers offers to more people, basically for free. Opendoor by contrast needs to acquire customers some other way.

Deals Made and Margin

As more offers are made, more deals are made. As more deals are made, Zillow learns more about how to operate this business and refines its ability to extract margin from the system. As it learns how to extract more margin, it can make more offers.

As you may have noticed in the image above, I crossed out leads and MLS deals. Zillow is majorly pissing off every real estate agent it has worked with, so while leads won’t go to zero, you can bet that agents will be more reluctant to work with Zillow than they were before.

Why did Zillow Start iBuying?

Back to the earlier questions, we can now start to think through why Zillow might have felt compelled to move from a perfectly fine flywheel to a significantly more complex one.

Option 1: The Top of the Funnel is Changing

One possibility is that Zillow recognized that the emergence of iBuying could lead to a new entry-point to the real estate discovery process. As real-estate analyst Mike DelPrete argued in iBuying Is Zestimate 2.0:

“The Zestimate was a lead generation tool that attracted consumers by giving them a starting point for determining what their home -- or any home -- is worth. It was online, it was fast, and it was easy...However, the entry of iBuyers with a service that made instant offers on a home – online – was novel and compelling, just like the Zestimate in 2006. Suddenly, more and more consumers were beginning their home selling process not on Zillow, but on other web sites like Opendoor and Offerpad...If you're in the business of providing consumers an estimate of the value of their home, the bar has just been set higher.”

If true, then it could be rational to invest billions of dollars in an iBuying business. But probably even more rational would be to either merge or partner with Opendoor, allowing each party to focus on what it was built to do.

Option 2: Romantic Vision of Zillow as Disruptor

Another possibility is that the original Zillow flywheel as described is, well, kind of boring. It is also not very disruptive. As Ben Thompson says, “Zillow did well to capture a portion of that 6% for itself through its realtor ad model, but that only meant that Zillow was as dependent on the status quo as the realtors.”

Rich Barton pines for the early days of Zillow when he set out to disrupt the real estate industry, which was then—as it is now—rife with inefficiencies, gatekeepers, and rent-seeking middlemen. Barton has talked about (most recently in this fantastic podcast episode) a desire to take the company back to its roots, and finally be the disruptor he had always believed Zillow to be.

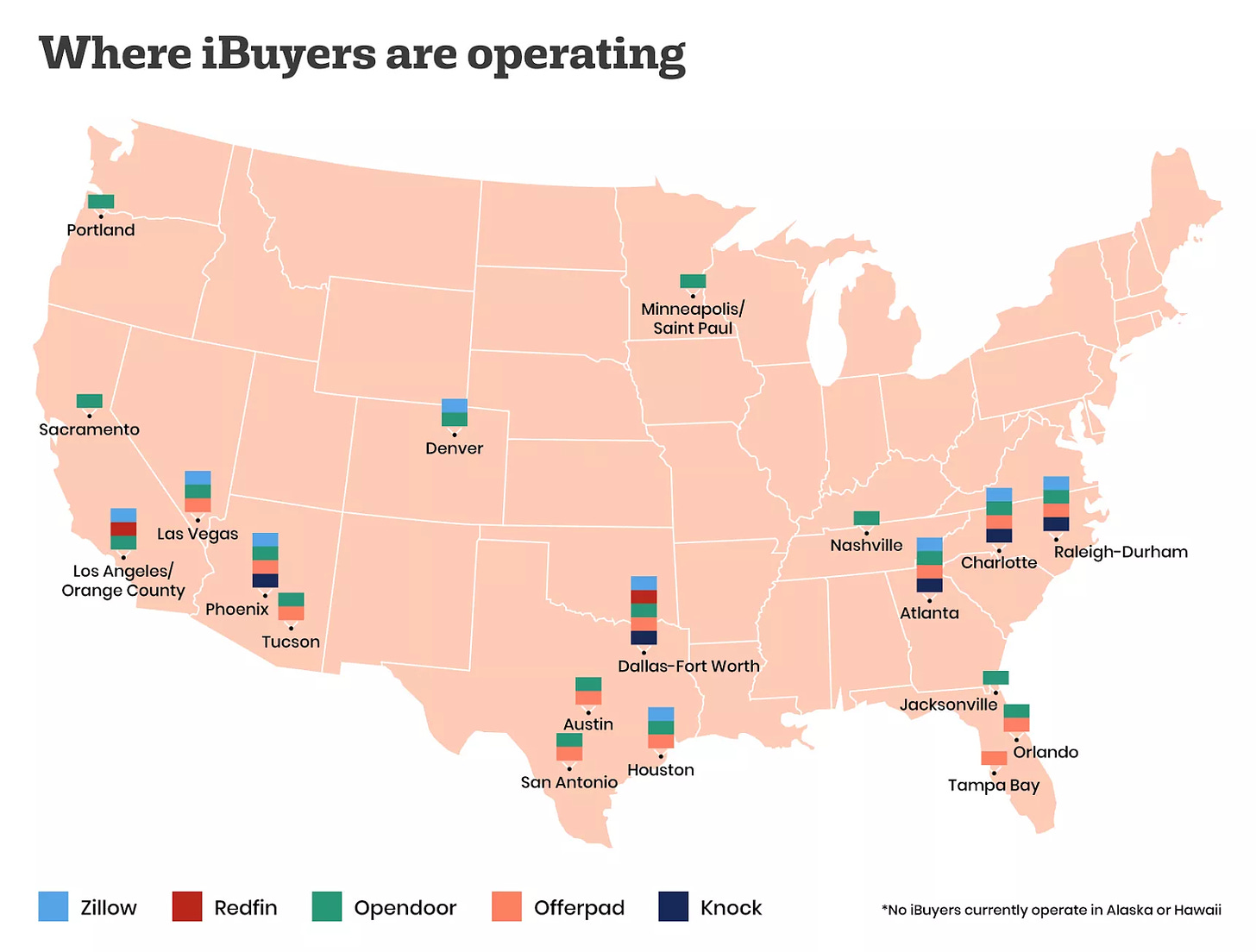

The only problem with this narrative is that it seems pretty clear that Zillow is just copying Opendoor. Don’t believe me? Take a look at the markets where iBuyers operate (as of March 2019, courtesy of Curbed):

Maybe this is truly the disruptive vision that Barton always held for Zillow, or perhaps when you operate a stable, mammoth cash cow you tend to have a failure of imagination around concepts like disruption.

Option 3: Failure of Imagination

That leads us to what I think is most likely. As we saw, Zillow faced the classic innovator’s dilemma: do you allow yourself to be disrupted by someone grazing on the edge of your field, or do you sacrifice your cow and attack the new entrant head-on?

It would have been impressive for Zillow to stay the course, patiently refining the original flywheel that led to such a high margin, high growth business as described at the top. The fact that they rejected that path to preempt a potential threat isn’t the problem in-and-of itself.

My gripe is the sheer failure of imagination. Zillow didn’t become a disruptor overnight, they built a copycat offering that is a poor fit for their original flywheel.

What would it look like to not have a failure of imagination? Packy McCormick wrote one of the most creative pieces I have read recently about what it might look like for Zillow and Airbnb to merge, and the disruptive features that would be unlocked:

“Over the past year as home buyers, Airbnb hosts, Airbnb guests, and now sellers, Puja and I have noticed places where a combined Airbnb and Zillow would complement each other perfectly. Try before you buy, access to lending based on Airbnb cash flows, rent to own, more accurate Zestimates, and click to buy are just a few of the things on our wishlist that could be solved in an Airbnb / Zillow merger.“

If Packy—who is undeniably smart but isn’t paid to think about Zillow all day for a living—could come up with such a high volume of creative ideas, then Zillow should also have been able to. In fact, the real estate market is so full of inefficiencies that you cannot convince me that iBuying was the only big idea Zillow could come up with to leverage the fact that 200 million people visit their site every month.

Wrapping Up

I don’t know if Zillow will be successful with Zillow Offers. The market is so huge that I have a hard time believing there’ll be only one winner. There’s more than enough space for both Zillow and Opendoor to grow large businesses in the space. But I do think that Zillow’s apparent lack of imagination is a sign that they shouldn’t be in that business. When a company has such a strong flywheel heading in one direction, it’s hard to suddenly start focusing on, or even concocting something entirely new.

We’ll never know what kind of business Zillow could have built had they chosen not to follow Opendoor, and rather found their own path that was uniquely Zillow. If they had chosen something that better fit their flywheel. My instinct is that Zillow could have become the disruptor—the innovator—Barton always wanted them to be, rather than an Opendoor copycat.

That’s it for this edition of The Flywheel. Thanks so much for reading. Don’t forget to vote!

A huge thanks to Tanya, Mom, Marni, and Lyle for helping with this one. If you liked this article, please subscribe and share with a friend!

What’s your take on Zillow? Share you thoughts with me on Twitter here.