Million Dollar Newsletter

It’s easy: all you need is 35,000 true fans.

Welcome to the new subscribers! If you’re reading this but haven’t subscribed, click below to join 2,734 of your smartest friends and peers who receive The Flywheel in their inbox every other Tuesday. More or less.

The last few weeks have been a roller coaster for me. I was in a major car accident (things are fine! Just shaken up), and my startup (Swapstack) started getting some great traction. Suffice it to say, my publishing schedule became a bit irregular over the past month or so. Thanks for your patience, and I look forward to getting back to a more regular schedule in the coming weeks and months! Onto the article.

Million Dollar Newsletter

A tweet from this past weekend caught my eye:

I had already planned to write an article about the recent creator craze, centered around Packy McCormick, author of the Not Boring newsletter, as a case study. This tweet, though, sets up the story better than I could have in my own words. Cheers, Packy, for tweeting the perfect setup for this piece without realizing it!

The tweet is perfect because it summarizes the key takeaways from Packy’s story (which I’ll tell later in this piece!), and in turn the broader creator thing happening right now:

Successful creators can make a lot of money,

They can have fun while doing it; and,

They almost, almost, can’t believe they get paid to do this.

We’ll take a deeper look into Packy’s recipe for success, but first let’s give some context on the “Creator Economy” movement, which has been the subject of some major buzz recently.

The Creator Economy

In recent years we’ve witnessed the rise of platforms that enable anyone to publish and monetize content online. In contrast to the pre-internet era, when gatekeepers like newspapers, music labels, movie studios, book publishers, and magazine editors determined who would and could become famous, this new ‘creator’ era has shifted that power to the scrolling thumbs of the crowd.

Regardless of the format, it is now easier than ever for enterprising folks to build an independent, online career. As Li Jin, one of the most prominent voices in this new economy, put it in her seminal piece on the Passion Economy: “Users can now build audiences at scale and turn their passions into livelihoods, whether that’s playing video games or producing video content. This has huge implications for entrepreneurship and what we’ll think of as a “job” in the future.”

Why? Probably a lot of reasons, but the main being that decade-long shifts in technology and society have led us here. Of course the internet is a core piece of it: as different business models have waxed and waned over the last two decades online, new methods of monetizing one’s own talents have emerged. In parallel, the idea of being ‘fulfilled’ in life has become mainstream over the past several decades. Getting paid is no longer enough; we strive for more in our daily lives than mere sustenance.

COVID came along in 2020 (remember?!) and poured rocket fuel on these long-brewing trends. Suddenly, with lives and careers upended, priorities revisited, and time at home in abundance, more people than ever tried their hands at the whole creator thing.

You might be wondering what, exactly, is a creator, as I did when I encountered the topic. The term is used loosely to describe anyone who publishes content online; and yet the term conjures up something far rarer, an artisanal quality that by definition isn’t accessible to everyone. When I hear the word creator I think of highly creative people like Lin Manuel Miranda, not someone who sends a few links in an email newsletter every week or so.

I was pleased to finally discover a definition that made sense to me, by Hugo Amsellem, in his excellent summary of the broader Creator Economy: “In a previous article, I argued that a creator isn't someone who creates but an individual who scales without permission. They are to the individual what startups are to the organization.” In other words, people who in eras past would have needed to go through a gatekeeper first.

This economy that’s sprouting up around them is in full force these days. As Packy conveniently wrote in a recent, super meta piece on this topic entitled Power to the Person:

The Passion Economy just keeps picking up momentum, and it’s reaching a fever pitch. While TikTok, YouTube, and Instagram keep exploding, new entrants are joining the party with breathtaking speed. In the past month alone:

Clubhouse raised its Series B at a $1 billion valuation and announced plans to let creators monetize directly from the audience through tips, tickets, or subscriptions.

Creator finance platform Stir raised its Series A at $100 million (a16z led both Clubhouse and Stir).

Substack announced that there are over 500,000 paid subscriptions on the platform, and that the top ten writers collectively make over $15 million.

Twitter acquired newsletter platform Revue.

YouTuber David Dobrik launched his photo app, Dispo, and it went so viral so quickly that it’s in talks to raise at its own $100 million valuation. (Read Divinations on Dispo).

LinkedIn (LinkedIn!!) is building a service called Marketplaces to compete with Fiverr and Upwork to connect freelancers and hirers.

Li unveiled her own $13 million early stage venture fund, Atelier Ventures, to invest in the Passion Economy (and instead of announcing in a major publication, she dropped the news in an interview in Lenny’s Newsletter).

That’s just the past month, and the list goes on.

There’s a vibrant movement of people all over the world shifting their careers, lives, and mindsets towards the Creator Economy, which may be as much an attitude as anything else. Those adopting this attitude are certain they are a product for which someone will pay, and I think observers are right that this will have profound effects on what we think of as a ‘career’ in the coming decades. More and more, people coming of age will believe (rightly or not) they may not need to go work a regular job for a regular company.

In many ways, I’ve been on this journey myself—quitting Amazon and starting The Flywheel and Swapstack (a direct result of my work on the newsletter) has been a shift towards the Creator Economy mindset.

The Multi-SKU Creator

Hunter Walk coined the term ‘The Multi-SKU Creator’, arguing that most creators won’t make 100% of their income from just one source. Using Casey Newton, author of Platformer, as an example, Walk writes:

“His beachhead may very well be a paid newsletter (it’s very good by the way) but the newsletter is just one SKU. Maybe the SKU he cares most about. Maybe even the SKU that makes him the most money. But it doesn’t have to be the only SKU. There could be a podcast SKU. A speaking fee SKU. A book deal SKU. A consulting SKU. A guest columnist SKU. And so on. And if he does several of these over the next few years, it won’t be about the success or failure of Substack (for him) but a mix of creative, economic and lifestyle goals.”

I think Walk is absolutely right about this, but it made me wonder how a creator should select which SKUs to offer in the marketplace. If I have a Substack newsletter, should I launch a podcast? Should I make a YouTube channel?

Creators have taken a wide array of approaches. Lenny Rachitsky started with a paid newsletter, added a community on top of it, and is now starting to offer paid courses. Mario Gabriele of The Generalist started with a series of free publications, added a community on top, and only recently has shifted to a paid subscription model. Mario’s approach has been unique because he’s leaned heavily on collaborations with other creators to publish an astonishing volume of highly diverse publications under The Generalist umbrella, which is well described in his recent interview with Alex Danco.

And this is just for writers. Just one other example to illustrate the point from TikTok land:

I might be biased, but I believe that creators would be well served to consider their portfolio of SKUs as a flywheel.

Step 1: figure out what the core of your engine is based on your business model.

Step 2: add SKUs that (1) are uniquely made better by your core activity (writing/TikToking, etc), and (2) that in turn feed back into that core activity and make it better/easier/more compelling over time.

One of my favorite examples of a creator treating their SKUs like a flywheel is Packy McCormick of the Not Boring newsletter.

I chatted with Packy for this piece—you can check out our conversation on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever else you download podcasts!

Packy has been on absolute fire since he rebranded his newsletter to Not Boring in March 2020. Take a look at his subscriber growth since he basically went full-time on this thing (note: this screenshot is a couple of weeks old; Not Boring is now up to over 36,000 as of last publish):

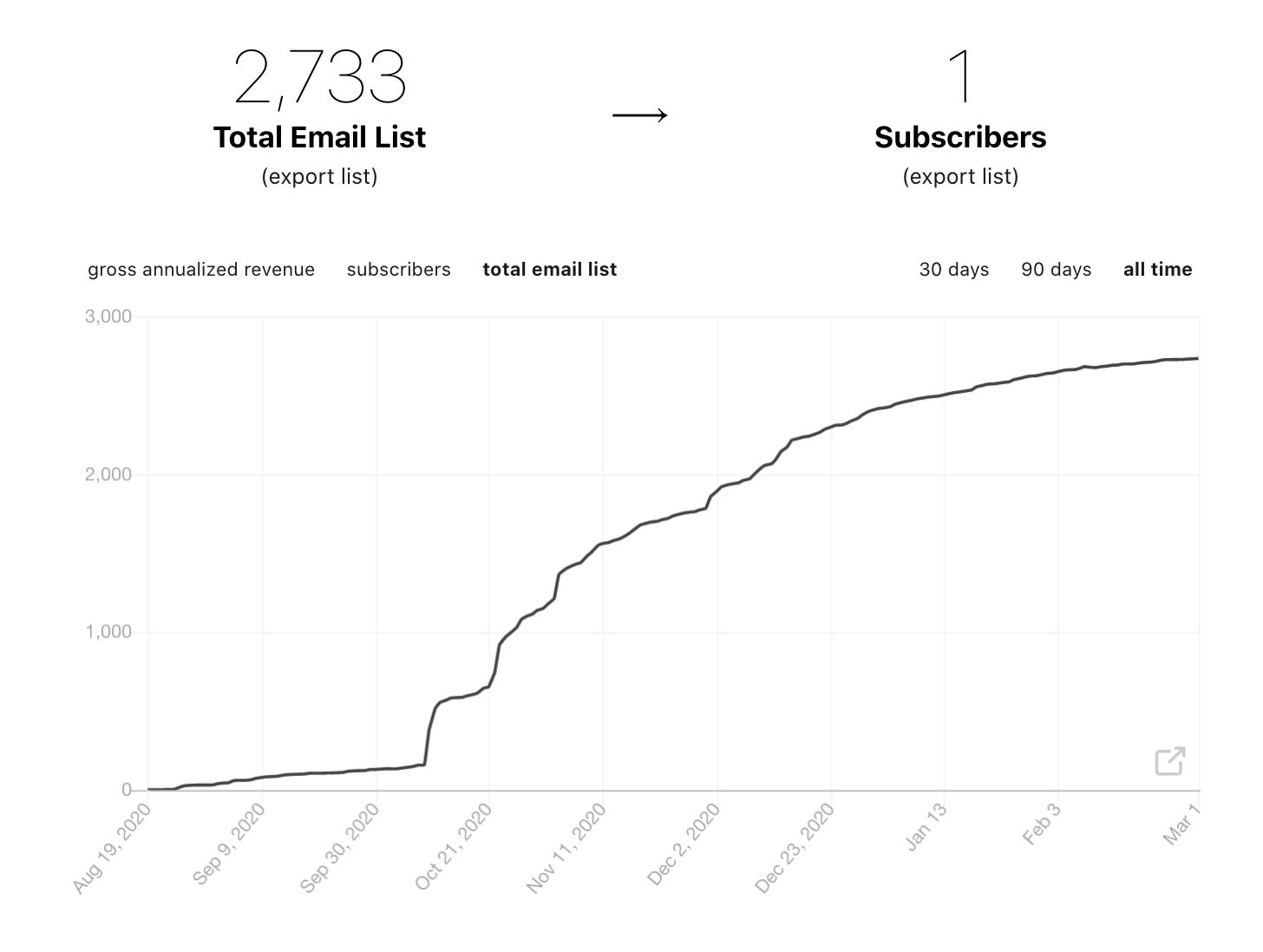

For context, here’s the graph for The Flywheel, which is generally considered to be a pretty successful newsletter in its own right:

It’s one thing to have a curve that looks like western slope of Mount Kilimanjaro; to sustain it for 10 months and counting is quite another.

Let’s dig in to Not Boring and the Packy McCormick flywheel:

Not Boring

What is it

Not Boring is a twice-weekly newsletter and angel investing syndicate run by Packy McCormick. The newsletter started sometime in 2019 under a different name (Per my last Email), and in 2020 Packy rebranded it to Not Boring. That’s when the fun began. It took a few months for Not Boring to find its voice; during that time, Packy experimented with different concepts like relating business concepts to those from pop culture. My favorite from this period was Packy’s essay about Hamilton and the potential for Disney to expand into education.

Towards late summer 2020, Not Boring’s essays got a little bit more serious, a little bit longer, and a little bit weedsier. Packy stopped worrying about what he thought would work, and instead started following his gut. In the process, Not Boring took off. I’ve already shown the subscriber graph, but it bears repeating. The Disney piece was sent to 5,000 people in July. His latest article about Jack Dorsey was sent to over 36,000 people. His readership has increased 620%+ in 8 months. If a startup had that kind of traction, it would be raising a unicorn round right now.

Not Boring has a few components:

Monday articles: these are Packy’s patented deep dives. Intended to be broadly appealing, Monday pieces might be 7,000 words about the metaverse, or about why FAAMG stocks are undervalued. These pieces have huge shareability, and indeed get shared quite a bit.

Thursday articles: these are reserved for a rotating selection of ‘alternative’ pieces, that fall into one of 2 categories: (1) investment memos on syndicate companies (more on this below), or (2) sponsored deep dives, in which a company pays up to $20,000 for Packy to break down its business and share it with 36,000+ smart readers.

Investing syndicate: Packy launched the ‘Not Boring Syndicate’ through AngelList to enable his readers to invest alongside him in companies. We’ll dive into this in the flywheel section below, but Packy cleverly marries his content with his investments to gain advantages on both.

Packy’s twitter account: though not formally part of Not Boring, Packy leverages his twitter account (with an equally steep follower count growth curve) to great effect. He’s funny and entertaining—or, not boring—and nice, all at the same time.

It’s worth noting that Not Boring is an extension of Packy’s personality. True to its name, the newsletter is indeed not boring. It stands out in the world of business analysis by virtue of its tone, vocabulary, self-deprecating nature, and informality.

The Business Model

Not Boring has bucked the trend of subscription everything and instead is designed to be supported by ads. In an ironic twist, Substack—ostensibly Not Boring’s publisher—will receive exactly $0 from Packy’s work so long as he resists the temptation to turn on the paywall.

Packy sells ads, primarily focused on SaaS companies, with roughly the following rate card:

Monday ad slot: $5,000 a pop

Thursday ad slot: $3,000 a pop

Sponsored deep dive: anywhere from $10,000-$20,000 for a full article dedicated to your company.

These are premium rates, and yet (at least according to Packy), no advertiser has yet regretted shelling out for a slot at the top of Not Boring.

Let’s do some math: if Packy earns $5,000 every Monday, and $3,000 or $15,000 every other Thursday, alternating, then he averages $14,000 per week, just from selling ads in his free newsletter.

As his subscriber count grows, so too will his rates, and we haven’t even discussed the upside he’s generating via his syndicate. This, folks, is how you build a million dollar newsletter, with even greater long-term upside.

The Flywheel

I wanted to write about Packy not only because he’s an inspiration to other newsletter writers like myself, but also because his portfolio of offerings weave together beautifully.

Packy is a better investor because of his writing, and he’s a better writer because of his investing. You can’t make up a better flywheel even if you tried:

The Monday Piece

The core of Packy’s flywheel is the Monday piece. These pieces are the crown jewel in Packy’s empire, the battery pack in his Tesla; these pieces are (rightly) shared en masse, and they fuel his obscene subscriber growth.

Audience Growth

As Packy’s keeps churning out hit after hit on Mondays, his audience doesn’t stop growing. Packy’s really transparent about all this, and he starts every article with something like this:

Look familiar? Please notice that he added 2,105 subscribers from last week to this week. 🤯 , indeed.

As the audience grows, a few things happen:

Founders turn to Packy to tell their story

Sponsors want to work with Packy

Founders

As Packy put it in our podcast conversation, he gets access to deals he has no business being in, simply because he will share the story with over 30,000 people. It doesn’t hurt that he lays bare his thought process over many thousands of words, presumably building credibility as a thinker along the way.

When founders approach Packy and they decide to work together, the result is a Thursday memo. In these pieces, Packy walks through how one might think through the prospect of investing in company X.

These memos are similar in spirit to sponsored deep dives; they are a deep look at a company, its industry, and its outlook. Sponsors see this and think to themselves..I might want one of those about me.

Sponsors

Audience growth leads to sponsor demand. More Thursday deep dives leads to more sponsor demand. More sponsored deep dives lead to more founder memo demand.

The kicker to all of this—what completes the flywheel—is how the Thursday memos and sponsored deep dives actually make the Monday pieces better. As a reminder, the Monday pieces are about topics that are in the zeitgeist, about big, famous, public companies. It’s hard to come up with something fresh to say about Amazon or Robinhood when everyone is writing about those same companies.

Packy’s Thursday work gives him an edge. He gets an inside look at how startups are approaching those very same industries. When he wrote about Robinhood, Packy had the benefit of his investment in Composer, access to its founders, and the memo he wrote about them.

The Creator Middle Class

We’ve looked at the playbook that outliers like Packy are writing,, but what does this suggest for the rest of us?

One flavor of popular creator economy analysis centers around the creator “middle class”. This typically refers to the idea that, sure, people like Packy might be able to have outsized success, but generally speaking creator platforms report that the top [insert small number] percent of creators account for [insert large number] percent of revenue. What happens to the rest of the creators who aren’t at the very top?

Li Jin cited a stat in a piece she wrote for her former firm a16z, that “according to a study of nine digital platforms (including Etsy, YouTube, and Twitch), 17 million Americans earned nearly $7 billion in income from their independent creations in 2017.” Her point was that the creator economy is growing, but if you do the math, that’s an average of $411 per creator.

Li is one of the thought leaders in this space—she recently left a16z to launch her own fund focused on creator economy companies—and she wrote the canonical piece about the creator middle class, and how platforms ought to think about enabling it.

I understand why platforms may want to establish a creator middle class—it’s not great for any platform to have its earnings concentrated in too few hands. Just ask Vine. Far better to sell the dream that anyone can make a living as a creator.

But what about from society’s perspective? Do we want everyone to be chasing a career as a creator? According to a creator economy rundown by VC firm Signal Fire, “more American kids want to be a YouTube star (29%) than an astronaut (11%) when they grow up.” Maybe this is fine, maybe it’s not.

Yes, it’s true that anyone can become a creator, but I think the lesson from cases like Packy is that not just anyone can turn it into a successful career. It reminds me of how my mom—a successful real estate broker—talks about how many millions of people get their real estate agent licenses. As she says, “anyone can get a real estate license. Not everyone can do something real with it.”

Like in real estate, it takes a combination of talent, personality, damn hard work, and flywheel-esque strategy that is extremely hard to pull off. Packy’s making it look easy, but he’s more talented than even he will admit. Is this a realistic standard—a realistic dream—to sell to everyone?

Check out my conversation with Packy McCormick about all things Not Boring:

That’s it for today’s edition of The Flywheel. Thanks a ton to Tanya and Jake for helping out with this one. Let me know what you thought of this piece by clicking one of the links below👇🏼.

Loved it • Liked it • Neutral • Not your best • Hated it

If you liked this article, smash that like button and share with a friend! Let me know your take on Twitter here.

Good stuff, thanks. Packy's a force of nature, great to watch him go and evolve in rapid iteration mode.

No doubt the creator economy is here to stay. But I think you hit the wheel with the fact that there's a number of variables that has to go hand in hand before succeeding. Just like musicians, artist, podcasters, youtubers or authors it's not enough to just be a good creator